About

In 2005, I skipped a day of work and drove to Palo Alto, California, to attend the International Lisp Conference at Stanford University. There, I briefly met John McCarthy, Turing Award winner, inventor of Lisp, and for all intents and purposes the closest thing to computer science royalty that exists. That was one of the highlights of my programming career.

At the time, my preferred programming language was Common Lisp. A few years earlier, I had read some of Paul Graham’s writings about Lisp and “drank the Kool-Aid.” After 25 years of programming in BASIC, assembly language, FORTH, C, C++, and Java, I finally found my way to Lisp and had that “Eureka!” moment where it all falls into place and your eyes are opened. (Though, to be honest, FORTH has some of the same transcendental qualities to it as Lisp does, but in a very different way.)

So, when I heard about this “new Lisp” in 2007, creatively named Clojure, with a “J,” that ran on the JVM, I was… unimpressed. “Are you kidding me?” I thought. “How can you take a fine programming language like Lisp and stuff it onto the Java virtual machine? That’s a step backwards! And this is 2007, for Pete’s sake, so how can you not even have proper tail recursion? Don’t these Clojure folks remember that lambda is the ultimate everything? If I wanted a Lisp on the JVM, I’d use Armed Bear Common Lisp or something like that. No thanks!”

That said, I did try to install it. But the early user experience was a bit… rough. Leiningen didn’t exist and running a Clojure program at the time was an annoying heap of classpath troubles. I was used to the relatively smooth Emacs + SLIME experience for programming in Common Lisp, and it would be a while before a port of SLIME to Clojure was available, never mind CIDER.

But, slowly and surely Clojure caught on and it grew, largely on the back of a really superior architecture. The JVM actually wasn’t a step backwards. Rather, it was a huge accelerator for Clojure’s adoption curve. It allowed Clojure to take advantage of one of the largest bodies of existing software, all the libraries written for Java. And after decades of production deployments, the JVM was fast. Sure, not as fast as well-written C, but really, really fast in comparison to Python and Ruby.

It would take me until maybe 2013 before I would try Clojure again in earnest and by that time, well, it was pretty darn good. Introductory books had been written. Leiningen was available. In short, most of the rough edges had been sanded down and it was a pretty smooth experience. Rather than getting tripped up and distracted by the rough spots, I could appreciate the beauty of the language itself.

And then, I started to watch some of Rich’s videos on YouTube. And it was clear that Clojure wasn’t just another personal, vanity version Lisp, thrown together willy-nilly. It didn’t have a bunch of random features piled one on top of another. And it wasn’t a “committee language” like Common Lisp. It had a lot of thought behind it. And Rich had a deep set of real-world experiences that were informing his choices. And when I listened to Rich explain why he had made those choices, it resonated with me. Many of his experiences matched my own. I found myself nodding along and saying, “Yep, that’s right.” Clearly, he was on to something.

And that’s when I began to get Clojure Crazy. If you’re a Lisp programmer, you already know what I’m talking about. There’s the “Eureka!” moment we all have. For me, that was in the early 2000s. You suddenly understand the power that Lisp brings and how that power is fundamental to the lambda calculus and programming itself. In my second Eureka moment, I realized that Clojure is Lisp for the modern age. It takes all the timeless magic of Lisp and energizes it with a focus on immutable values that takes Lisp up another notch. While Clojure wouldn’t have been viable on the slow machines with limited memory that were the norm in the 1960s, it is The Right Answer for programming in the 2000s, with multi-gigahertz, multi-core systems with gigabytes of memory. And that’s just your mobile phone, never mind your laptop or server.

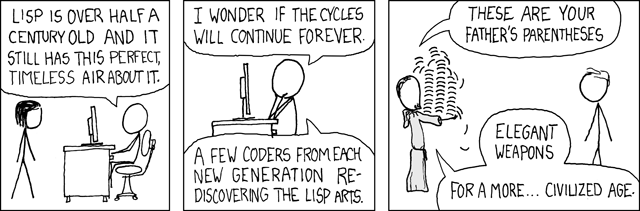

In short, the classic XKCD comic is not wrong:

Lisp is timeless, precisely because there is almost nothing to it. McCarthy’s first Lisp interpreter from the late 1950s can fit on a page, single sided. Alan Kay, one of the inventors of object-oriented programming, Smalltalk, and himself a Turing Award winner described Lisp as the “Maxwell’s equations of software.” While Clojure is certainly a bit more complex (some would say “sophisticated”) than the original single-page Lisp interpreter, its changes and additions come from the same source.

So, this blog is an exploration of Clojure and the magic that it brings to the programming party.

Enjoy! And feel free to drop me a note with comments or suggestions.